How Dharma was born as Vidura due to Mandayva’s curse

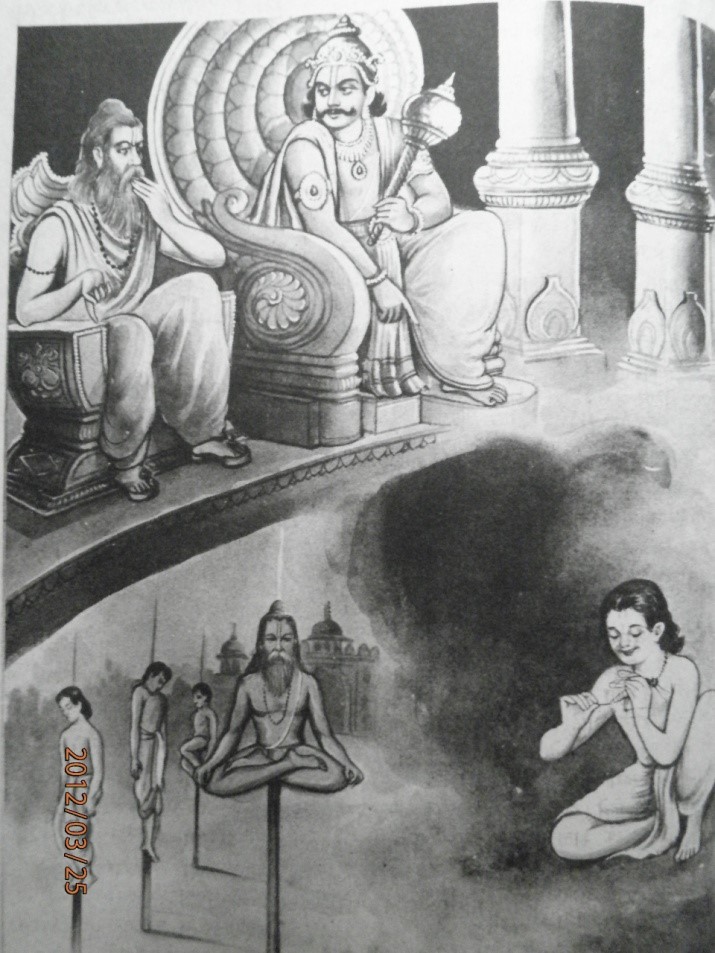

There was a Brahmana known by the name of Mandavya. He was conversant with all duties and was devoted to Dharma, truth and asceticism. The great ascetic used to sit at the entrance of his hermitage at the foot of a tree, with his arms upraised in the observance of the vow of silence. As he sat there for years together, one day there came into his Ashrama a number of robbers laden with spoil. Those robbers were then being pursued by a superior body as guardians of the peace. The thieves, on entering that Ashrama, hid their booty there, and in fear concealed themselves thereabout before the guards came. But scarcely had they thus concealed themselves when the constables in pursuit came to the spot. The latter, observing the Rishi sitting under the tree, questioned him, saying, “O best of Brahmanas, which way have the thieves taken? Point it out to us so that we may follow it without loss of time.” Thus questioned by the guardians of peace the ascetic, said not a word, good or otherwise, in reply. The officers of the king, however, on searching that Ashrama soon discovered the thieves concealed thereabout together with the plunder. Upon this, their suspicion fell upon the Muni, and accordingly they seized him with the thieves and brought him before the king. The king sentenced him to be executed along with his supposed associates. The officers, acting in ignorance, carried out the sentence by impaling the celebrated Rishi. Having impaled him, they went to the king with the booty they had recovered. But the virtuous Rishi, though impaled and kept without food, remained in that state for a long time without dying. The Rishi by his ascetic power not only preserved his life but summoned other Rishis to the scene. They came there in the night in the forms of birds, and beholding him engaged in ascetic meditation though fixed on that stake, became plunged into grief. Telling that best of Brahmanas who they were, they asked him saying, “O Brahmana, we desire to know what has been your sin for which you has thus been made to suffer the tortures of impalement!”

Thus asked, the tiger among Munis then answered those Rishis of ascetic wealth, “Whom shall I blame for this? In fact, none else (than my own self) has offended against me!” After this, the officers of justice, seeing him alive, informed the king of it. The latter hearing what they said, consulted with his advisers, and came to the place and began to pacify the Rishi. fixed on the stake. The king said, “O best of Rishis, I have offended against you in ignorance. I beseech you to pardon me for the same. It beholds you not to be angry with me.” Thus addressed by the king, the Muni was pacified. Beholding him free from wrath, the king took him up with the stake and endeavoured to extract it from his body. But not succeeding therein, he cut it off at the point just outside the body. The Muni, with a portion of the stake within his body, walked about, and in that state practised the austerest of penances and conquered numberless regions unattainable by others. For the circumstances of a part of the stake being within his body, he came to be known in the three worlds by the name of Ani-Mandavya (Mandavya with the stake within). One day that Brahamana acquainted with the highest truth of Dharma went unto the abode of the god of Dharma. Beholding the god there seated on his throne, the Rishi reproached him and said, “What, pray, is that sinful act committed by me unconsciously, for which I am bearing this punishment? Tell me soon, and behold the power of my asceticism.”

The god of Dharma, thus questioned, replied, “O you of ascetic wealth, a little insect was once pierced by you on a blade of grass. You bear now the consequence of the act. O Rishi, as a gift, however small, multiplies in respect of its religious merits, so a sinful act multiplies in respect of the woe it brings in its train.” On hearing this, Ani-Mandavya asked, “Tell me truly when this act was committed by me. Told in reply by the god of justice that he had committed it, when a child, the Rishi said, “That shall not be a sin which may be done by a child up to the twelfth year of his age from birth. The scriptures shall not recognise it as sinful. The punishment you has inflicted on me for such a venial offence has been disproportionate in severity. The killing of a Brahmana involves a sin that is heavier than the killing of any other living being. You shall, therefore, O god of Dharma, have to be born among men even in the Sudra order. From this day I establish this limit in respect of the consequence of acts that an act shall not be sinful when committed by one below the age of fourteen. But when committed by one above that age, it shall be regarded as sin.

Cursed for this fault by that illustrious Rishi, the god of Dharma had his birth as Vidura in the Sudra order. Vidura was well-versed in the doctrines of morality and also politics and worldly profit. He was entirely free from covetousness and wrath. Possessed of great foresight and undisturbed tranquillity of mind, Vidura was ever devoted to the welfare of the Kurus.