Rishyashringa

Rishyashringa, of dreaded name, was born as a son to Vibhandaka, who was a Brahmana saint, who had cultured his soul by means of religious austerities, whose seed never failed in causing generation, and who was learned and bright like the Lord of beings. The father was highly honoured, and the son was possessed of a mighty spirit, and, though a boy, was respected by aged man. That son of Kashyapa, Vibhandaka, having proceeded to a big lake, devoted himself to the practice of penances. That same saint, comparable to a god, laboured for a long period. Once while he was washing his mouth in the waters, he beheld the celestial nymph Urvasi, whereupon came out his seminal fluid. A hind at that time lapped it up along with the water that she was drinking, being athirst; and from this cause she became with child. That same hind had really been a daughter of the gods, and had been told of yore by the holy Brahma, “You shall be a hind; and when in that form, you shall give birth to a saint; you shall then be freed.” As Destiny would have it, and as the word of the creator would not be untrue, in that same hind was born Vibhandaka's son a mighty saint. Rishyashringa, devoted to penances, always passed his days in the forest. There was a horn on the head of that magnanimous saint and for this reason did he come to be known at the time by the name of Rishyashringa. Barring his father, not a man had ever before been seen by him; therefore his mind was entirely devoted to the duties of a continent life.

At this very period there was a ruler of the land of Anga known by the name of Lomapada who was a friend of Dasharatha. He from love of pleasure had been guilty of a falsehood towards a Brahmana. That same ruler had at that time been shunned by all persons of the priestly class. He was without a ministering priest to assist him in his religious rites. Indra suddenly abstained from giving rain in his territory; so that his people began to suffer and he questioned a number of Brahmanas, devoted to penances, of cultivated minds, and possessed of capabilities with reference to the matter of rain being granted by the lord of gods, saying, “How may the heavens grant us the rain? Think of an expedient for this purpose.” Those same cultured men, being thus questioned, gave expression to their respective views. One among them spoke to that same king, saying, “O lord of kings! the Brahmanas are angry with you. Do some act for appeasing them. Send for Rishyashringa, the son of a saint, resident of the forest knowing nothing of the female sex, and always taking delight in simplicity. If he, great in the practice of penances, should show himself in your territory, forthwith rain would be granted by the heavens, herein I have no doubt at all.”

Having heard these words, Lomapada made atonement for his sins. He went away; and when the Brahmanas had been appeased, he returned again, and seeing the king returned, the people were again glad at heart. Then the king of Anga convened a meeting of his ministers, proficient in giving counsel. He took great pains in order to settle some plan for securing a visit from Rishyashringa. With those ministers, who were versed in all branches of knowledge, exceedingly proficient in worldly matters, and had a thorough training in practical affairs, he at last settled a plan. Then he sent for a number of courtesans, women of the town, clever in everything. When they came, the king spoke to them, saying, “You lovely women! You must find some means to allure, and obtain the confidence of the son of the saint, Rishyashringa, whom you must bring over to my territory.”

Those women, on the one hand afraid of the anger of the king and on the other, dreading a curse from the saint, became sad and confounded, and declared the business to be beyond their power. One, however, among them, a hoary woman, thus spoke to the king, “O great king! Him whose wealth solely consists in penances, I shall try to bring over here. You will, however, have to procure for me certain things, in connection with the plan. In that case, I may be able to bring over the son of the saint Rishyashringa.” Thereupon the king gave an order that all that she might ask for should be procured. He also gave a good deal of wealth and jewels of various kinds. Then, she took with herself a number of women endowed with beauty and youth, and went to the forest without delay.

She, in order to compass the object of the king, prepared a floating hermitage, both because the king had ordered so, and also because it exactly accorded with her plan. The floating hermitage, containing artificial trees adorned with various flowers and fruits, and surrounded by diverse shrubs and creeping plants and capable of furnishing choice and delicious fruits, was exceedingly delightful, nice, pleasing, and looked as if it had been created by magic. Then she moored the vessel at no great distance from the hermitage of Kashyapa's son, and sent emissaries to survey the place where that same saint habitually went about. Then she saw an opportunity; and having conceived a plan in her mind, sent forward her daughter, a courtesan by trade and of smart sense. That clever woman went to the vicinity of the religious man and arriving at the hermitage beheld the son of the saint.

The courtesan said, “I hope, O saint! that is all well with the religious devotees. I hope that you have a plentiful store of fruits, roots and that you take delight in this hermitage. Verily I come here now to pay you a visit. I hope the practice of austerities among the saints is on the increase. I hope that your father's spirit has not slackened and that he is well pleased with you. I hope you prosecute the studies proper for you.”"

Rishyashringa said, “You are shining with lustre, as if you were a mass of light. I deem you worthy of obeisance. Verily I shall give you water for washing your feet, such fruits and roots also as may be liked by you, for this is what my Dharma has prescribed to me. Be you pleased to take at your pleasure your seat on a mat made of the sacred grass, covered over with a black deer-skin and made pleasant and comfortable to sit upon. Where is your hermitage? O Brahmana! You resemble a god in your mien. What is the name of this particular religious vow, which you seem to be observing now?”

The courtesan said, “O son of Kashyapa! On the other side of yonder hill, which covers the space of three Yojanas, is my hermitage, a delightful place. There, not to receive obeisance is the rule of my faith nor do I touch water for washing my feet. I am not worthy of obeisance from persons like you; but I must make obeisance to you. O Brahmana! This is the religious observance to be practised by me, namely, that you must be clasped in my arms."

Rishyashringa said, “Let me give you ripe fruits, such as gallnuts, Karushas, Ingudas from sandy tracts and Indian fig. May it please you to take a delight in them!"

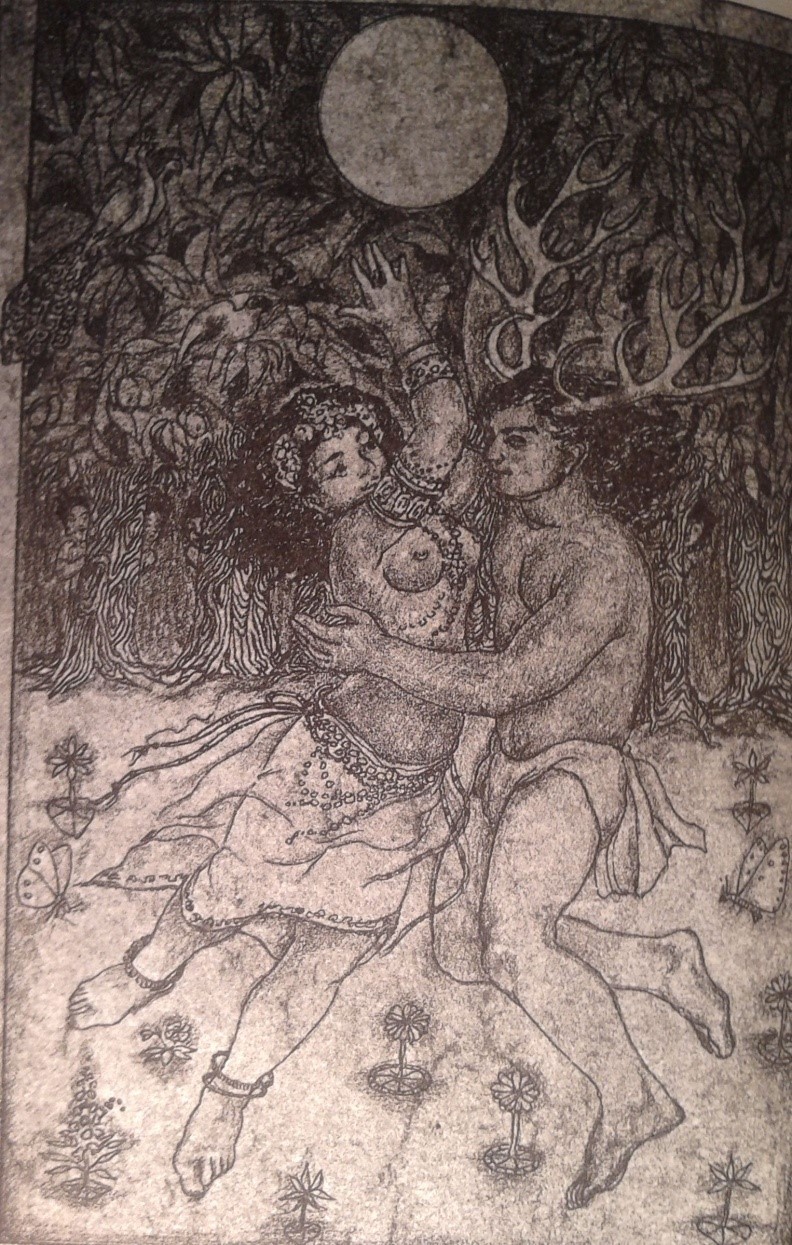

She, however, threw aside all those edible things and then gave him unsuitable things for food. These were exceedingly nice and beautiful to see and were very much acceptable to Rishyashringa. She gave him garlands of an exceedingly fragrant scent, beautiful and shining garments to wear and first-rate drinks; and then played, laughed and enjoyed herself. She at his sight played with a ball and while thus employed, looked like a creeping plant broken in two. She touched his body with her own and repeatedly clasped Rishyashringa in her arms. Then she bent and break the flowery twigs from trees, such as the Sala, the Ashoka and the Tilaka. Overpowered with intoxication, assuming a bashful look, she went on tempting the great saint's son. When she saw that the heart of Rishyashringa had been touched, she repeatedly pressed his body with her own and casting glances, slowly went away under the pretext that she was going to make offerings on the fire. On her departure, Rishyashringa became over-powered with love and lost his sense. His mind turned constantly to her and felt itself vacant. He began to sigh and seemed to be in great distress.

At that moment appeared Vibhandaka, Kashyapa's son, he whose eyes were tawny like those of a lion, whose body was covered with hair down to the tip of the nails, who was devoted to studies proper for his caste, and whose life was pure and was passed in religious meditation. He came up and saw that his son was seated alone, pensive and sad, his mind upset and sighing again and again with upturned eyes. Vibhandaka spoke to his distressed son, saying, “My boy! Why is it that you are not hewing the logs for fuel. I hope you have performed the ceremony of burnt offering today. I hope you have polished the sacrificial ladles and spoons and brought the calf to the milch cow whose milk furnishes materials for making offerings on the fire. Verily you are not in your wonted state, O son! You seem to be pensive, and to have lost your sense. Why are you so sad today? Let me ask you, who has been to this place today?"

Rishyashringa said, “Here came to-day a religious student with a mass of hair on his head. He was neither short nor tall. He was of a spirited look and a golden complexion, and endued with eye large as lotuses; he was shining and graceful as a god. Rich was his beauty blazing like the Sun; and he was exceedingly fair with eyes graceful and black. His twisted hair was blue-black, neat, long, of a fragrant scent and tied up with strings of gold. A beautiful ornament was shining on his neck which looked like lightning in the sky. Under the throat he had two balls of flesh without a single hair upon them and of an exceedingly beautiful form. His waist was slender to a degree and his navel neat; and smooth also was the region about his ribs. Then again there shone a golden string from under his cloth, just like this waist-string of mine. There was something on his feet of a wonderful shape which give forth a jingling sound. Upon his wrists likewise was tied a pair of ornaments that made a similar sound and looked just like this rosary here. When he walked, his ornaments uttered a jingling sound like those uttered by delighted ganders upon a sheet of water. He had on his person garments of a wonderful make; these clothes of mine are by no means beautiful like those. His face was wonderful to behold; and his voice was calculated to gladden the heart; and his speech was pleasant like the song of the male blackbird. While listening to the same I felt touched to my inmost soul. As a forest in the midst of the vernal season, assumes a grace only when it is swept over by the breeze, so, he of an excellent and pure smell looks beautiful when fanned by the air. His mass of hair is neatly tied up and remains adhering to the head and forehead evenly sundered in two. His two eyes seemed to be covered with wonderful Chakravaka birds of an exceedingly beautiful form. He carried upon his right palm a wonderful globur fruit, which reaches the ground and again and again leaps up to the sky in a strange way. He beats it and turns himself round and whirls like a tree moved by the breeze. When I looked at him, O father! he seemed to be a son of the celestials, my joy was extreme, and my pleasure unbounded. He clasped my body, took hold of my matted hair, and bent down my mouth, and, mingling his mouth with my own, uttered a sound that was exceedingly pleasant. He does not care for water for washing his feet, nor for those fruits offered by me; and he told me that such was the religious observance practised by him. He gave unto me a number of fruits. Those fruits were tasteful unto me: these here are not equal to them in taste. They have not got any rind nor any stone within them, like these. He of a noble form gave me to drink water of an exceedingly fine flavour; and having drunk it, I experienced great pleasure; and the ground seemed to be moving under my feet. These are the garlands beautiful and fragrant and twined with silken threads that belong to him. He, bright with fervent piety, having scattered these garlands here, went back to his own hermitage. His departure has saddened my heart; and my frame seems to be in a burning sensation! My desire is to go to him as soon as I can, and to have him every day walk about here. O father! Let me this very moment go to him. Pray, what is that religious observance which is being practised by him. As he of a noble piety is practising penances, so I am desirous to live the same life with him. My heart is yearning after similar observances. My soul will be in torment if I see him not.”

Vibhandaka said, “Those are, O son! Rakshasas. They walk about in that wonderfully beautiful form. Their strength is unrivalled and their beauty great They always meditate obstruction to the practice of penances. O my boy! They assume lovely forms and try to allure by diverse means. Those fierce beings hurled the saints, the dwellers of the woods, from blessed regions. The saint who has control over his soul, and who is desirous of obtaining the regions where go the righteous, ought to have nothing to do with them. Their acts are vile and their delight is in causing obstruction to those who practise penance; a pious man should never look at them. O son! Those were drinks unworthy to be drunk, being as they were spirituous liquors consumed by unrighteous men. These garlands, also, bright and fragrant and of various hues, are not intended for saints.”

Having thus forbidden his son by saying that those were wicked demons, Vibhandaka went in quest of her. When by three day's search he was unable to trace where she was he then came back to his own hermitage. In the meanwhile, when the son of Kashyapa had gone out to gather fruits, then that very courtesan came again to tempt Rishyashringa in the manner described above. As soon as Rishyashringa had her in sight, he was glad and hurriedly rushing towards him said, “Let us go to your hermitage before the return of my father.” Then, those same courtesans by contrivances made the only son of Kashyapa enter their bark, and unmoored the vessel. By various means they went on delighting him and at length came to the side of Anga's king. Leaving then that floating vessel of an exceedingly white tint upon the water, and having placed it within sight of the hermitage, he similarly prepared a beautiful forest known by the name of the Floating Hermitage. The king, however, kept that only son of Vibhandaka within that part of the palace destined for the females when of a sudden he beheld that rain was poured by the heavens and that the world began to be flooded with water.

Lomapada, the desire of his heart fulfilled, bestowed his daughter Shanta on Rishyashringa in marriage. With a view to appease the wrath of his father, he ordered kine to be placed, and fields to be ploughed, by the road that Vibhandaka was to take, in order to come to his son. The king also placed plentiful cattle and stout cowherds, and gave the latter the following order: "When the great saint Vibhandaka should enquire of you about his son, you must join your palms and say to him that these cattle, and these ploughed fields belong to his son and that you are his slaves, and that you are ready to obey him in all that he might bid.”

Now the saint, whose wrath was fierce, came to his hermitage, having gathered fruits and roots and searched for his son. But not finding him he became exceedingly wroth. He was tortured with anger and suspected it to be the doing of the king. Therefore, he directed his course towards the city of Champa having made up his mind to burn the king, his city, and his whole territory. On the way he was fatigued and hungry, when he reached those same settlements of cowherds, rich with cattle. He was honoured in a suitable way by those cowherds and then spent the night in a manner befitting a king. Having received very great hospitality from them, he asked them, saying, “To whom do you belong?” Then they all came up to him and said, “All this wealth has been provided for your son.” At different places he was thus honoured by that best of men, and saw his son who looked like the god Indra in heaven. He also beheld there his daughter-in-law, Shanta, looking like lightning issuing from a cloud. Having seen the hamlets and the cowpens provided for his son and having also beheld Shanta, his great resentment was appeased. Vibhandaka expressed great satisfaction with the king. The great saint, whose power rivalled that of the sun and the god of fire, placed there his son, and thus spoke, “As soon as a son is born to you, and having performed all that is agreeable to the king, to the forest must you come without fail.”

Rishyashringa did exactly as his father said, and went back to the place where his father was. Shanta obediently waited upon him as in the firmament the star Rohini waits upon the Moon, or as the fortunate Arundhati waits upon Vasishtha, or as Lopamudra waits upon Agastya. As Damayanti was an obedient wife to Nala, or as Shachi is to Indra or as Indrasena, Narayana's daughter, was always obedient to Mudgala, so did Shanta wait affectionately upon Rishyashringa, when he lived in the wood.

Lovely discription